Examining the delusions of Dawkins

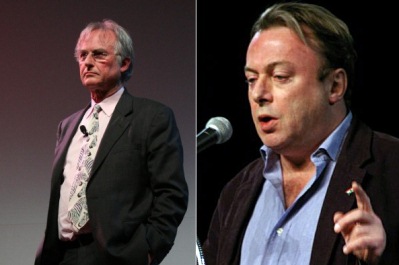

Regular Network Norfolk columnist James Knight dissects the popular arguments of atheists Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens on God, religion and faith and argues that they do not stand up well to scrutiny. This week Richard Dawkins.

Regular Network Norfolk columnist James Knight dissects the popular arguments of atheists Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens on God, religion and faith and argues that they do not stand up well to scrutiny. This week Richard Dawkins.

When it comes to discussions about God, I've often been baffled at how it is that Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens, arguably the two most prominent atheist spokesmen in recent times, have got away with speaking so much nonsense for so long, while all the time enjoying adulation, approbation and lionisation by an ever-increasing group of followers and imitators.

So, finally getting round to it, I thought I'd go to Google-search to find what has been offered as their 'best' quotes against God, religion and faith, and show why they don't stand up to rigorous scrutiny.

As you'll see, Dawkins and (next time out) Hitchens have ready-made methods for twisting meanings and distorting logic in a way that the more pliant and impressionable individuals don't seem to notice.

To pick one common example, there is this little linguistic sleight of hand: simply pick the word of which you want people to disapprove - brainwash, faith (taken to mean belief without evidence), dictatorship, tyranny, barbaric, etc. - and then describe the particular word in terms that your readers already disapprove of, apply it in blanket form to the thing you're attacking, and you'll find you have them on your side. Alternatively, simply pick a word you know people like - evidence, reason, freedom, science, etc. - and apply it to your own agenda, and you'll have people believe you're offering a genuine progression that they are compelled to support (politicians do both these things all the time).

Let's start with a humorous observation. One of Richard Dawkins' well known quotes is this one:

"The take-home message is that we should blame religion itself, not religious extremism - as though that were some kind of terrible perversion of real, decent religion. Voltaire got it right long ago: 'Those who can make you believe absurdities can make you commit atrocities.”1

True, but judging by the absurdities we are now going to see, are we to conclude that in endorsing Voltaire, Richard Dawkins could make his fans commit atrocities? Probably not, but although Dawkins can't make his fans commit atrocities, he certainly does help them with fallacies and misjudgements as the following quotes from him will show.

"Where does Darwinian evolution leave God? The kindest thing to say is that it leaves him with nothing to do, and no achievements that might attract our praise, our worship or our fear. Evolution is God's redundancy notice, his pink slip."2

Notice what Dawkins does here; in conveying the power of evolutionary theory as an explanatory agent for the diversity of life on this planet, he offers a fact that has nothing to do with the issues surrounding God's existence or non-existence, and then he draws a conclusion that employs poor reasoning and absurdity in its imaginative failings. Biochemical evolution almost certainly explains all life on earth, from abiogenesis, through to the rich and diverse complexities of life we see after a few billion years of natural selection. But biological evolution doesn't imply that God has nothing to do - that's as silly as saying that filling a hotel with staff and guests implies that there was nothing for the planners and builders to do in constructing the hotel.

Biological evolution only explains the relatively easy part - that is, once we have the laws of physics, the mathematical underpinnings, and the informational platform, then biological life, once it gets going, is a relatively straightforward step by step cumulative selection process, certainly in comparison to creating a universe and designing the complex physical laws that act as a canvas for the colours and textures of evolution of life. The hard part is in explaining why the universe is made of mathematics, and why there is any mathematics at all, and why anything so complex exists in the first place. That Dawkins makes such a crass misjudgement in ignoring the hard part to point us to the easy part suggests to me he is either being insincere or he is engaging in out and out intellectual buffoonery.

"One of the truly bad effects of religion is that it teaches us that it is a virtue to be satisfied with not understanding."3

As it stands this is another meaningless statement. Only if he places the word 'sometimes' between the words 'it' and 'teaches' does the sentence have any bearing on reality - and even then it only amounts to the tautology of 'Sometimes religion teaches people to be satisfied with not understanding and sometimes it doesn't'. Dawkins really only means that one of the truly bad effects of religion is that it sometimes teaches people that it is a virtue to be satisfied with not understanding. Yes, and one of the truly bad effects of going to school is that some pupils fail their exams due to general under-achievement and insufficient study. Does that mean schools are a bad thing? No.

Everyone knows the reason why. Many pupils achieve good grades because they are endowed with curiosity and diligence and they embrace learning. What does that say about schools? That they operate on a 'you get out what you put in' basis. That's just what one would expect of a religion too - 'you get out what you put in'. Religious teachers that teach adherents to be satisfied with not understanding are of course noxious, but equally there are many religious teachers, as well as religious precepts, institutions, and works of literature and non-fiction, that greatly enrich the mind and engender a greater creative intellect.

"Faith is the great cop-out, the great excuse to evade the need to think and evaluate evidence. Faith is the belief in spite of, even perhaps because of, the lack of evidence."

Here's how Dawkins makes this statement work - he changes the word 'faith' to mean something that is generally thought to be bad (evading the need to think and evaluate evidence) and makes an appeal based on that fabrication (this is a popular trick employed by politicians too). If that were an accurate depiction of faith, then Dawkins would be right to criticise it, just as if my depiction of the historical record of Hitler was an accurate depiction of Martin Luther King then I'd be right to criticise Martin Luther King for Hitler's crimes. Hopefully, though, if I started criticising Martin Luther King on grounds that he invaded Poland, Belgium, France, Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union, oversaw Nazi concentration camps, and was responsible for the death of millions of people, you'd rightly pull me up as being under a misapprehension.

Similarly, with Dawkins, faith is not what he paints it to be. Having faith says little about someone's willingness to evaluate evidence, as evidence for anything empirical is confined only to the classes of object that are part of the physical substrate (be they physics, biology, economics, and so forth). Having faith is to have an interpretation of reality as a whole - an interpretation that all things connected to the physical substrate are part of a much bigger Divine plan, and that through the Incarnation we can trust that God's plan is being played out. Faith has nothing to do with the kind of evidence Dawkins means when he uses the word.

"Do you really mean to tell me the only reason you try to be good is to gain God's approval and reward, or to avoid his disapproval and punishment? That's not morality, that's just sucking up, apple-polishing, looking over your shoulder at the great surveillance camera in the sky"4

This is an example of a statement that has universal appeal, but in having such low-hanging appeal it really says nothing compelling at all. I don't know any believer in God who lives a life of such bereft and tremulous servitude that they would only do good because of gaining approval, Divine or elsewhere. There probably are religious people for whom this is the case, just as there are people who are ultra-servile towards other humans (North Korea being a good example). But most educated, thoughtful believers understand that morality is an evolved phenomenon (as is the need for approval), and that moral imperatives are both beneficial and necessary for human survival and fruitful co-existence, irrespective of whether one believes in God or not. That Dawkins peddles this distortion suggests either he doesn't understand why people believe in God or it suggests that he is trying to mislead people (perhaps a bit of both).

"There is something infantile in the presumption that somebody else has a responsibility to give your life meaning and point... The truly adult view, by contrast, is that our life is as meaningful, as full and as wonderful as we choose to make it."5

This is an example of a statement that contains a false dichotomy and also two false assumptions. The first false assumption is that to be a theist means living a childish life in which believers simply delegate all responsibility onto others in some puerile manner. That obviously isn't the case - theists have faith and trust in an all-powerful God, but as far as day to day living is concerned they understand that life is full of personal responsibility; and, of course, many take it upon themselves to go the extra few miles and campaign for social justice and global changes inspired by Christ's instructions.

The second false assumption is that it is 'infantile' to presume that 'somebody else has a responsibility to give your life meaning and point'. If we take out the overly-emotive word 'responsibility' we all know that it is other people that do give our lives meaning - there's nothing to be ashamed of in acknowledging this, and certainly nothing exclusive to theism here. We all rely on each other for love, friendship, knowledge, aspiration, a sense of purpose and so forth, even Richard Dawkins does. Place those two false assumptions together and you'll see Dawkins has created a false dichotomy.

"The universe we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil and no good, nothing but blind pitiless indifference."6

How does Richard Dawkins know what the difference would be between properties in a universe that is designed and properties in a universe that isn't designed? He can't know this, because if this universe is created then its properties that we observe are created properties, and if it isn't created then its properties that we observe are naturalistic. Dawkins, like all humans, has no conceptual wherewithal of any ontological distinction between the two types of universe.

As an illustration, if a dressmaker states that a particular piece of clothing has been sewn wrong, then her argument is rational because she has a clear idea of what the correct stitch pattern should look like. If we make the same claim regarding our universe - if we say that the universe is not fine-tuned, or that it was not created by a God, and has 'just the wrong kind of stitch pattern', then we must know what a wrong stitch pattern is in relation to a right one. As far as we know, nature could have brought about that same stitch pattern in a created universe or a naturalistic universe, so there are no grounds for such an assertion by Dawkins, as we humans have no information about God that allows us to conclude that only a certain stitch pattern is a God-created one.

Another point; Dawkins presumably doesn't really think that there is nothing but 'blind pitiless indifference' in his ontological enquiries; he presumably thinks that he has created meaning and purpose to his own life. Therefore, I presume he'll willingly admit that all humans are able to create their own meaning and purpose as well, which means that at the very least the universe has created billions of creatures who each have developed deep concepts of meaning and purpose, which goes to show that there is quite a bit more than blind pitiless indifference in nature, and that the question of whether those deep concepts relate to even deeper truths not yet understood is not a matter that has been resolved.

"So it is best to keep an open mind and be agnostic. At first sight that seems an unassailable position, at least in the weak sense of Pascal's wager. But on second thoughts it seems a cop-out, because the same could be said of Father Christmas and tooth fairies. There may be fairies at the bottom of the garden. There is no evidence for it, but you can't prove that there aren't any, so shouldn't we be agnostic with respect to fairies?"7

This is the sort of emotional propaganda that seeks to manipulate readers by conflating two concepts as though they are one interchangeable entity - things that are genuinely believed to be real (like God) and things that are acknowledged by anyone above the age of 6 or 7 to be fantastical fabrications (like Santa Claus). Santa Claus is made up by parents for kids' enjoyment. Philosophy of religion, metaphysics, and arguments for and against God's existence amount to a long, broad and deep enquiry that has preoccupied human thinking for millennia, and continues to do so. I wonder if anyone has ever asked Richard Dawkins why he and his fellow cronies are not out there debating Santa Claus. If he tells you that that's an entirely different realm of discourse to philosophy of religion, metaphysics, and arguments for and against God's existence then you'll be entitled to ask what valuable point he thinks he's making by treating those two different things as though they are the same in the above sentence.

Of course, Dawkins thinks they (God and Santa Claus) are the same by being non-existent, but that is to commit the fallacy of begging the question, which is assuming the conclusion of an argument (that God does not exist) when that is the question being discussed and at the very heart of humans' life enquiry. It's as silly as saying that opium makes us tired because it has sleep-inducing properties, or smoking causes cancer because it has cancer-inducing properties. It is one thing to find a causal link (which we certainly have in the case of smoking and cancer) - it is quite another to foolishly assume a conclusion in the sentence before the causal links have even been found.

"I am against religion because it teaches us to be satisfied with not understanding the world."8

Or my own paraphrase: I'm against Richard Dawkins because he teaches his admirers to be satisfied with not understanding poor arguments. Or if we stick to his exact words we see they are so general as to be meaningless. Even if we ignore Dawkins' failure to define what it means to 'understand the world', what about all the religious people that understand the world better than Richard Dawkins, what does he suppose that religion taught those people?

Such generalisations are hopelessly misjudged, as any sensible person, theist or non-theist, would rightly repudiate the notion of being satisfied with not understanding the world. What Dawkins really means is, people who don't share my views don't understand the world as well as I do, which really only amounts to an unsubstantiated, ego-stroking statement that carries no weight, and not the least bit of decisiveness.

"The feeling of awed wonder that science can give us is one of the highest experiences of which the human psyche is capable. It is a deep aesthetic passion to rank with the finest that music and poetry can deliver. It is truly one of the things that make life worth living and it does so, if anything, more effectively if it convinces us that the time we have for living is quite finite."9

Notice the false assumption here - the wonder of science convinces us that the time we have for living is finite. Why does it? Being startled by science simply means being startled by discoveries about the physical universe, all of which amount to physical creatures making discoveries about other physical phenomena. Those discoveries say nothing about whether there is more to reality than the physical, so by definition they cannot inform us of whether our existence will be finite. They may indicate that our physical existence is ultimately finite, but the Christian faith also expresses that view, so that's not really saying anything against religious belief.

But there is a further point to consider. Although natural selection may have endowed us with the mental resources necessary for survival, reproduction, safety, status and learning - what strikes me as incredible about the human mind is that these aren't the things it finds most fascinating. It finds more fascinating the things that one might consider to be subsidiary facets to human life. In other words, it isn't the necessary things like food, water, oxygen, sunlight, or copulation that fill us with awe - it is the unnecessary things in our evolution like love, beauty, sublimity, music, poetry, literature, art, faith, the picturesque natural world and the astounding mathematical patterns in nature that really fill us with awe. They are the things we really wouldn't want to be without. Although we shouldn't diminish our appreciation for the natural world, it really does feel at times like we were created for another world altogether and that this life is a disquisition attached to some greater narrative.

Perhaps that is what the writer of Ecclesiastes means when he says that 'God has set eternity in our hearts'. Not that we should fail to marvel at nature and enjoy this life, but that we should marvel and enjoy her in preparation for something even better. Either way, there are no grounds for using studies of a physical universe to project ideas about finitude.

Lastly, I want to comment on another common error that is often made by atheists - the assumption that God needs no defining and can just be talked about without recourse to clear definition of concepts and ideas. In his book The God Delusion, Richard Dawkins made this classic error when he produced his popularly received seven point scale – a 1-7 valuation of the strength of belief or disbelief in God. Here it is:

1. Strong Theist: : I am 100% sure that there is a God

2. De-facto Theist: I cannot know for certain but I strongly believe in God and I live my life on the assumption that he is there.

3. Weak Theist: I am very uncertain, but I am inclined to believe in God.

4. Pure Agnostic: I don’t know about God’s existence or non-existence, so am undecided.

5. Weak Atheist: I do not know whether God exists but I’m inclined to be skeptical.

6. De-facto Atheist: I cannot know for certain but I think God is very improbable and I live my life under the assumption that he is not there.

7. Strong Atheist: I am 100% sure that there is no God.10

In stating where on the scale he sits, Dawkins says “I count myself in category 6, but leaning towards 7. I am agnostic only to the extent that I am agnostic about fairies at the bottom of the garden.” In other words, Dawkins is fairly unequivocally an atheist with not much room for change. The reality is, his 1-7 scale exhibits the kind of flawed thinking that even nascent first year philosophy students would see as absurd. Here’s what is wrong with the model. As an indicator of strength of belief, the model is entirely meaningless because strength of belief is inextricably linked to whether one’s position is philosophically good or bad, and whether one has any reasonable justification for belief in God. In other words, anyone can tell you where his strength of belief sits on a made up scale of 1-7, but it is only worth taking seriously if the person expressing the belief has a competent understanding of the subject and a good philosophical brain with which to reason.

As well as the model failing to pay any regard to the competency of the person doing the grading, here’s what else is wrong with Richard Dawkins’ attempts to grade belief in God on a scale of 1-7. The primary fault is that he didn’t even make the slightest mention of the fact that belief in God or gods is just about the most diverse subject out there, and that such an evaluation should be based on a hugely complex and varied mix of experiential protocols to which he’s given no consideration. It is not simply that the 1-7 scale must be brought to bear in consideration for every instance of conceived God or gods in the world (although that is still one criticism), because I assume the strength of belief for the Christian God would hardly be sensibly compared to, say, the Baha’i god, or one of the African rain gods. But even if we allow that to a rational and intelligent mind all the gods in the world have co-equivalence in being able to be rejected, the 1-7 scale is completely circular because it only gives expression of the rejection of the concept of God that each person has in their mental toolbox. Rejection of God by a man who has very little competence in the subjects of faith, theology, belief and philosophy has almost no meaningfulness.

The truth is, there is not one unique 1-7 scale that Dawkins has created for us all to take a shot at, there has to be one for every single person in the world, because everybody’s conception, experiences, ideas and mental abilities are different. If Richard Dawkins realised this, he’d realise the ineffectuality of his 1-7 model. Even if we allow that one concept of God for every human is a bit excessive, it has to at least be acknowledged that an attempt to construct a scalar model of belief and treat is as a unique metric for philosophical returns is about as narrow-minded and parochial as it gets. What the Dawkins model does is treat people as though they all see religious belief in the same way and with the same ability, and it treats the ‘God’ concept as though it is homogenous in structure, when it’s about the least homogenous concept around.

Next time out I will examine the thoughts and quotes of Christopher Hitchens, a much slipperier customer

James Knight is a long term contributor to the Network Norwich & Norfolk website and a local government officer based in Norwich.

The views carried here are those of the author, not of Network Norwich and Norfolk, and are intended to stimulate constructive debate between website users.

James Knight is a long term contributor to the Network Norwich & Norfolk website and a local government officer based in Norwich.

The views carried here are those of the author, not of Network Norwich and Norfolk, and are intended to stimulate constructive debate between website users.

We welcome your thoughts and comments, posted below, upon the ideas expressed here.

Click here to read our forum and comment posting guidelines

You can also contact the author direct at j.knight423@btinternet.com

1. Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion

2. Richard Dawkins, Man vs God, Wall Street Journal

3. Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion

4. Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion

5. Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion

6. Richard Dawkins, River Out of Eden

7. Richard Dawkins, From speech at the Edinburgh International Science Festival

8. Richard Dawkins, From speech at the Edinburgh International Science Festival

9. Richard Dawkins, Unweaving the Rainbow: Science, Delusion and the Appetite for Wonder

10. Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion